Currently Empty: ৳ 0.00

THE EXTRAORDINARY LIFE OF SALVADOR DALÍ

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

EARLY LIFE:

After the death of their firstborn, Dalí’s parents gave him the name ‘Salvador’ after his deceased brother. Later at the age of five, he was told that Dalí was the reincarnation of his brother, which left an everlasting impression on him. Dalí came to believe the concept and later said in an interview “we resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections. ‘He’ was probably the first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute.” His parents encouraged him to study art at a very early age. A year after his mother’s death, Dalí moved into a student residence in Madrid at the age of 17 and continued studying fine arts. Soon after, he started experimenting with Cubism and because of his intricate craftsmanship and technical skills, Dalí started gaining popularity. He was doing exceptionally well in academia but was later expelled days before the final exams in 1926 when he stated that no one on the faculty was competent enough to examine him. Later in 1929, he went to Paris and began interacting with artists such as Picasso, Magritte, and Miró, which led to Dalí’s first Surrealist phase.DALÍ ’S JOURNEY INTO SURREALISM:

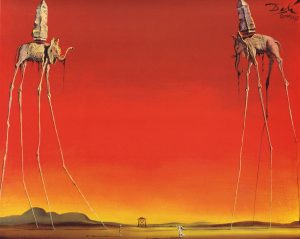

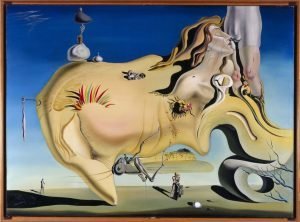

Surrealism indicates the form of a cultural movement in visual expressions and literature, which gained immense popularity in Europe between the two World Wars. The movement represented a reaction against what its individuals saw as the destruction wrought by rationalism which had shaped history, art, and politics; it was characterized by unexpected juxtapositions in ordinary scenes that challenge the viewer’s imagination. It emphasized the total reunification of the conscious and unconscious realms of experience through the means of lucid dreaming and hypnotism, to the point where the world of dream and fantasy would be joined to the everyday rational world in “a superior form of reality; surreality.”

“Surrealism is destructive, but it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision,”– Salvador Dalí

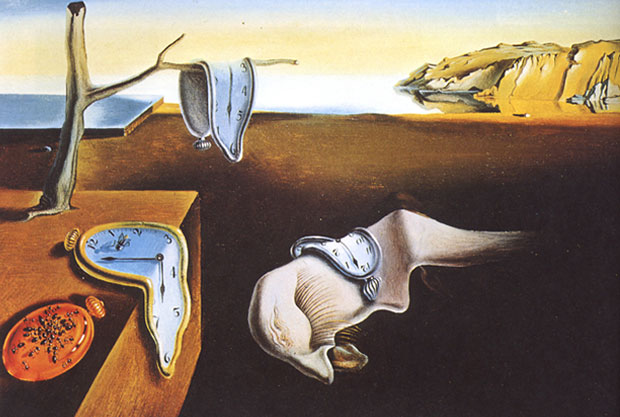

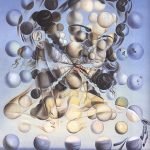

“I do not paint a portrait to look like the subject, rather does the person grow to look like his portrait.”A major part of the Surrealist movement was based on the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud and Dalí had his share of fascination towards knowing the subconscious self and what could be revealed by his dreams. After his discovery of Freud’s writings on the erotic significance of the subconscious imagery, Dalí deliberately started indulging in hallucinatory states within himself. And once he had skillfully done so, his painting style matured at an extraordinary rate. This helped him reach his peak artistic creativity from the year 1929 to 1937. These are the times when he created some of his greatest artworks. In his trance state, he used to see commonplace items in a very contrasting nature, deformed or otherwise in metamorphosed condition and he used to include these figures in his drawing as meticulously as possible. From which, emerged his most famous piece of artwork, The Persistence of Memory in 1931.– Salvador Dalí

Source: www.mutualart.com

DALÍ ’S SYMBOLISM:

Considered as his most famous painting, The Persistence of Memory became an overnight sensation on its debut exhibition in New York, in January 1932. Renowned art dealer and Gallerist Julien Levy explained the painting as a “10 by 14 inches of Dalí dynamite”. Levy was the owner of Julien Levy Gallery in New York City, an important venue for Surrealists, avante-garde artists and American photographers in the 1930s and 1940s.

Source: WikiArt.org

Dalí in America: Desire for Money, Fame & Hollywood:

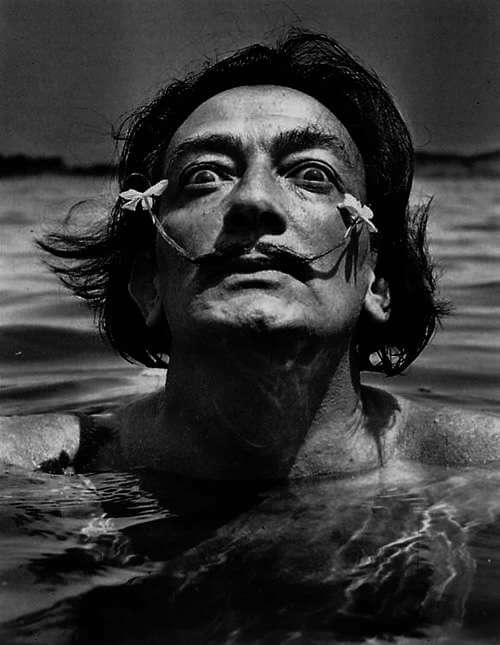

When the Second World War broke out, Dalí had to flee from Europe and settled in the United States, where he remained until 1948. During his eight year stay in the states, Dalí gained an immense popularity and got the anagrammatic nickname “Avida Dollars”. He always had a yearning for money and worked in whichever project that earned him a good buck. From designing shop windows for Fifth Avenue and collaborating on set design for ballets to working on Hollywood films like Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound, and Walt Disney’s Destino, he did it all. He even authored two books: Hidden Faces (1944) and The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942). Influenced by the seventeenth-century Spanish master painter Diego Velazquez, Dalí grew a flamboyant mustache, which later became an iconic image of him. His rebellious nature and rejection of the ordinary gained so much attention that his face somewhat became a global icon and a widely used pop-culture reference. Even in the popular Netflix crime drama Money Heist (Spanish: La casa de Papel, “The House of Paper”), we get to see the main characters wearing Dalí Masks as a symbol of Resistance.

Source: Netflix

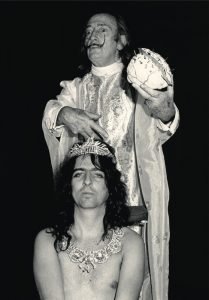

“When you wear that mask you start seeing the world from a different perspective. To me, that’s the symbol of the wonderful craziness Dalí had in his life”It comes as no surprise that Salvador Dalí had a lot of famous friends like Elvis Presley, John Lennon, David Bowie, Pablo Picasso, and even Sigmund Freud. But probably his strangest acquaintance was with the controversial rock legend Alice Cooper.-Itziar Ituno (Raquel)

Source: www.dailyartmagazine.com

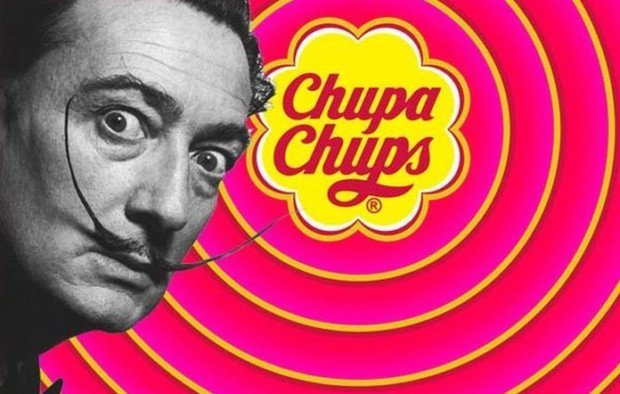

“In 1969, Dalí was approached to design a new Chupa Chups logo, and the result became as instantly recognizable as his melting clocks. Dalí incorporated the Chupa Chups name into a brightly colored daisy shape. Always keenly aware of branding, Dalí suggested that the logo be placed on top of the lolly instead of the side so that it could always be seen intact.”-Quoted from BBC’s Modern Masters: Dalí, Chupa Chups logo

Fascination with Hitler, Sexuality & Political Ambiguity:

Dalí’s interest in erotic neuroses and death, together with his eerie portrayal of fear, influenced his distinctive brand of surrealism, mixing classic techniques with avant-garde subject matter and laying the groundwork for future generations of artists. While the use of Dalí’s abject subject matter, such as the projection of sexual encounters or bodily fluids, bothered his fellow surrealists, it was the artist’s unwillingness to condemn fascism in the mid-1930s which ultimately resulted in his excommunication from the group.

“The difference between the Surrealists and me is that I am a Surrealist”His blatant self-love was publicly denounced by the English writer and critic George Orwell, who criticized Dalí’s autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí with an essay entitled “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí”. Orwell defined the autobiography as “a strip-tease act conducted in pink limelight” and pointed out Dalí’s character, describing him as “an unmistakable assault on sanity and decency.”

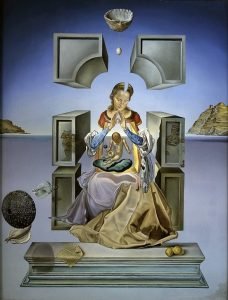

Courtesy: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Legacy and Recognition:

Many of Dalí’s admirers get bummed about how his eccentric and extravagant public behavior at times attracted more attention than his artwork while a lot of his critics feel irritated just by hearing his name. There has been a lot of controversy over his public support for the Francoist regime, his commercial activities as well as the quality and authenticity of some of his late works. Either way, we cannot deny the influence his life and work had on other Surrealists, pop art, and contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst. There are two major museums devoted to his work: The Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain and the Salvador Dalí Museum in Florida. For his unparallel contribution to art, he received a number of recognitions.

Courtesy: Patrick Chabert/Flickr

- 1964: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- 1972: Associate member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium

- 1978: Associate member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut de France

- 1981: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III

- 1982: Created 1st Marqués de Dalí de Púbol, by King Juan Carlos

Life Lessons from Salvador Dalí:

Salvador Dalí has led an exciting life and even if he was an oddball, we can learn a thing or two from this legendary artist.1. Take art history and make it your own

Dalí may be known primarily as a surrealist, but he was actually a restless experimenter, working in many different styles and mediums throughout his career. As a young man, he shamelessly appropriated elements from other movements, including impressionism, pointillism, cubism, fauvism, purism and futurism with great skill.2. Learn from your mistakes

“Mistakes are almost always of a sacred nature. Never try to correct them. On the contrary: rationalize them, understand them thoroughly. After that, it will be possible for you to sublimate them.”– Salvador Dalí

3. Love thy self

“Every morning when I wake up, I experience an exquisite joy — the joy of being Salvador Dalí — and I ask myself in rapture, ‘What wonderful things is this Salvador Dalí going to accomplish today?”– Salvador Dalí

4. It’s okay to have a change of heart

“At the age of six I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since”– Salvador Dalí

5. Never stress out over the little things

“Have no fear of perfection- you’ll never reach it”– Salvador Dalí

Final Days:

After the death of his wife in 1982, Dalí lost much of his will to live, and purposely dehydrated himself almost to the point of death. In 1984, a mysterious fire broke out in his apartment. Luckily, he was saved but many suspected it as a suicide attempt. He eventually succumbed to heart failure and met his end at the age of 84, five years after that incident. Dalí even insisted on being buried at his own Theater-Museum in Figueres when he died in 1989, in a lifelong demonstration that art and man are inseparable for the artist as well as his audience.

Photograph by Philippe Halsman. Source: Wikimedia Commons

“There is only one difference between a madman and me. The madman thinks he is sane. I know I am mad.”– Salvador Dalí

He was a madman indeed, but a genius madman nevertheless.