Currently Empty: ৳ 0.00

Klimt: The Seduction of Gold

Austrian artist Gustav Klimt is one of the most celebrated Symbolist artists, widely recognized for his technique of incorporating patterns and metallic colors into his artworks. He was a true master of this rather unusual art style. From “The Kiss” which ranks amongst the most passionate embraces in history, to his stunning portrait of the wealthy society lady Adele Bloch-Bauer, draped in gold (commonly referred to as the Lady in Gold/ Woman in Gold). Klimt was a revolutionary in nature and immensely gifted in skill. His exquisite Femme Fatales and risque imagery added to the traditional sensibilities of Vienna at the end of the 19th to early 20th century and turned the Austrian artist into a controversial icon.

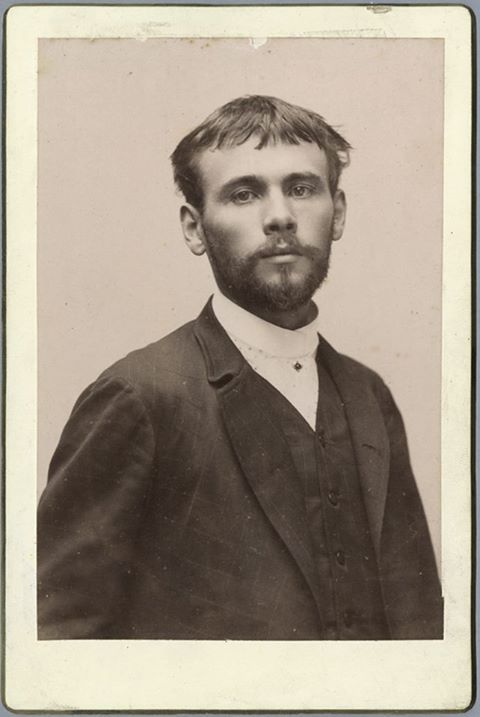

With his monumental artworks and promiscuous personal life, Gustav Klimt has been an everlasting subject of fascination amongst everyone, even to this day. One could easily get fooled by his unusual get-up in photographs depicting a sort-of bearded hippie draped in floor-length tunics supposedly without anything underneath, cradling his most beloved cat Katze. With an infamous intrigue in the female body both on and off the canvas, Klimt’s studio was the site of as many masterpieces as it was of hushed affairs, his continuous attempt to avoid scandals, combined with his visionary Eva overflowing with sexually charged illustrations, yielded life and a legacy of enticing speculations as he not only just made the lustrous paintings draped in gold that we all are used to seeing, he had quite a few series of vividly erotic sketches in his collection as well.

“All art is erotic.”

― Gustav Klimt

EARLY AGE:

Klimt was born to a poor family of seven children in a small village just outside Vienna in 1862. His father had engraved gold for a living, an influence which would manifest itself within Klimt’s congenital artisanal eye, and presumably result in his repeated use of gold leaf later on in his work.

Between 1862 and 1884, the Klimts moved frequently, living at no fewer than five different addresses, always in search of cheaper living facilities. Amidst all the financial struggle, the Klimt family had to experience a great tragedy in 1874 when Klimt’s younger sister, Anna, died at the age of five after succumbing to illness. Not long after, his sister Klara suffered a mental breakdown after succumbing to religious fervor.

At an early age, Klimt and his two brothers Ernst and Georg displayed obvious artistic promise. Gustav, however, was singled out by his instructors as an exceptional draftsman while attending secondary school. In October 1876, at the age of fourteen, he was accepted to the Kunstgewerbeschule, the Viennese School of Arts and Crafts.

TRAINING AND FIRST RECOGNITION:

During his time in Kunstgewerbeschule, he acquired exceptional technical skills in architectural and figurative drawing and began picking up early commissions of painting portraits from photographs in his spare time. While he was preparing to teach drawing professionally, one of his professors awarded him, his younger brother Ernst (who also attended the School of Applied Arts) and another student by the name of Franz von Matsch with an extended scholarship in decorative painting. In 1879, the Klimt brothers along with Matsch established their first workshop called the “Company of Artists” and found considerable success by getting commissioned to create murals based on mythology, history, plays, and operas in theaters, museums, and palaces across Vienna. Klimt was awarded the Golden Order of Merit for his exceptional work in Vienna’s Burgtheater in 1888 by the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef (I). While these large-scale, public paintings were initially rendered in an academic style and featured classical subject matter, many of them foreshadowed Klimt’s role in the Secessionist Movement—and his subsequent shift into the avant-garde Golden Phase.

TRANSITION TO AVANT-GARDE:

Klimt lived through a critical and fragmented period in the history of Vienna. While the progressive ideals of Vanguard artists and intellectuals collided with the traditions of the establishment of the old world, Klimt drew inspiration from both past and present. He was a great admirer of the famous Viennese historical painter of the time, Hans Makart, and in particular his technique, that used dramatic contrasts of light and his apparent love for theatricality and vision. At one point, when still a student, Klimt reportedly bribed one of Makart ‘s servants to let him enter the painter’s studio so that Klimt could research the new projects in progress. He was also intrigued by the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their early symbolist style and Japanese woodblock prints as well as Sigmund Freud, who talks about death, anxiety, and sex as the driving forces behind human behavior.

“On my first days here I did not start work immediately but, as planned, I took it easy for a few days – flicked through books, studied Japanese art a little.”

―Gustav Klimt

As he began exploring the creative freedom outside the academy, his style became increasingly Avant-grade as a sign of maturity. The deaths of his brother Ernst and his father the elder Ernst both in 1892 had a profound effect on his desire to investigate the intricacies of human emotion and to work unfettered by what society deemed appropriate. When he was commissioned by the Kunsthistorisches Museum to paint a mural chronicling the history of art, he chose to populate the timeline with poised female subjects. The project served as a gateway to Klimt’s famous femme Fatales, seductresses. His open embrace of eroticism would progressively shock and offend his patrons. In 1894 he accepted a one-off Commission to paint allegories of philosophy, medicine, and law for the University of Vienna but his panels were condemned for their indecency. Klimt was furious and vowed to reject all future government commissions. In 1897, Klimt joined forces with a group of like-minded artists to co-found an uncensored art movement known as the Vienna Secession. They mingled and revolted against realism and naturalism and art as well as Vienna’s insular nationalistic art institutions. Rather, they embraced the exchange of international styles and the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk or Total Artwork, which unified fine art, decorative art, and architecture.

By rejecting Vienna’s traditionally conservative art scene, Klimt and other Secessionists gave Vienna’s contemporary artists a platform to share their work freely. This liberating movement inspired and allowed Klimt to experiment with his art and develop a Symbolist style inspired by the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements.

As his painting style became increasingly modern, his approach to the material did, too. During the movement’s early years, Klimt began incorporating gold leaf into his works, marking the start of a new chapter, one that would forever set him apart from the artists of the world.

THE GOLDEN PHASE:

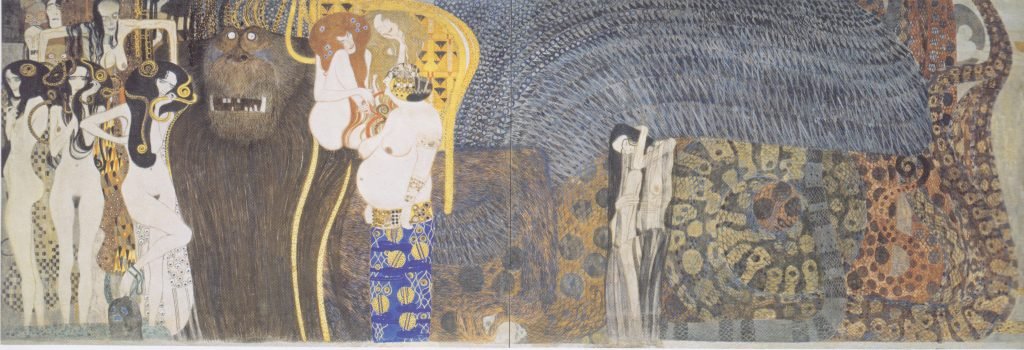

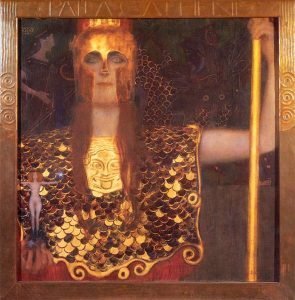

Klimt served as the secessions’ first president and created several magnificent paintings during his leadership including Pallas Athene, Judith and the Head of Holofernes and the Beethoven Frieze; a mural painted on the walls of the dedicated Vienna secession building where it remains to this day. With the completion of Pallas Athene in 1898, it marked the beginning of Klimts’ so-called golden phase. Throughout this phase, he made a number of instantly recognizable paintings punctuated by gold geometric decorations and bursting flora.

Klimt delved further into his Golden Phase with the Beethoven Frieze in 1902. With this 112-foot-long wall loop which was initially planned for the 14th Vienna Secessionist exhibition, he paid a tribute to the German composer and pianist Ludwig van Beethoven by creating a visual interpretation of his Ninth Symphony. It also features opulent planes, mystical patterns and figures, and ornamental accents that have become iconic features of Klimt’s golden works of art.

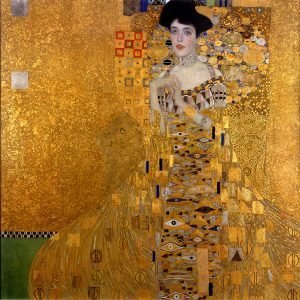

The majority of the phases’ artworks were heavily influenced by Byzantine mosaics that Klimt saw during a trip to Italy in 1903, after which, he painted three of his most famous gilded masterpieces; Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, The Stoclet Frieze, and The Kiss.

As a renowned painter and prominent figure in Vienna’s contemporary art scene, Klimt often got commissions for painting portraits of the capital city’s upper-class women. The most famous among these compositions is the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), a painting showcasing the wife of a rich Jewish banker. While this piece depicts one of Klimt’s real-life contemporaries, its lavish use of gold gives it an otherworldly appearance, reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics, highlighting the timeless beauty of the “new Viennese woman.”

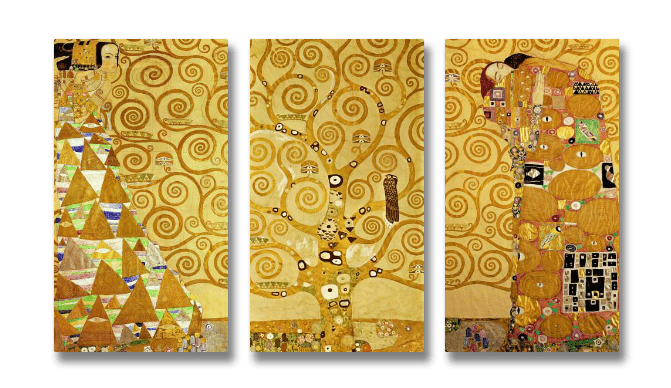

Klimt separated with secessionists in 1905 after the group had broken up because of differing ideas on where and how to concentrate their artistic endeavors. During the same year, Klimt began working on the Stoclet Frieze, a series of three extravagant mosaics commissioned for the dining room of the Stoclet House in Brussels. The focal point of the entire set is the Tree of Life, a stylized portrayal of a tree with swirling, spiraling branches, intricate pattern-work, and symbolic motifs inspired by ancient art. The tree is complemented by figures, including an elegant dancer and a couple that bears a striking resemblance to the lovers featured in The Kiss. Created in 1911 as an iconic symbol of the golden age, namely for the dancer as The Expectation, the couple as The Embrace with the Tree of Life in the middle, Stoclet Frieze is hailed as one of the most valuable decorative works of art to have ever been made.

Arguably Klimt’s most famous work, The Kiss was completed in 1908. The painting lives inside the Belvedere museum in Vienna, Austria. And it’s perfectly square in shape, measuring nearly six feet on each side. In the painting, you will see a woman kneeling with her body in profile, while her head tilts to face its’ viewer. Her head is firmly held in the hands of the man whos face hovers above her. One of her hands curls around his and the other drapes around his neck. Her skin is pale while in contrast, his’ is ruddy in complexion. Her eyes are closed. And we see just a portion of his face as he plants his kiss while she embraces him ever-so-gently. They are both in extravagantly designed outfits, his voluminous coverall shrouded in rectangular patterns, and hers is a slender frame with rounded shapes. They’re surrounded by flowers on the edge of a hill with her legs curled over the edge. Everything else around them is gold, a nebulous, shimmering atmosphere that puts them in a trance-like state, completely oblivious of time and space, lost in each other’s arms.

“Truth is like fire; to tell the truth means to glow and burn.”

― Gustav Klimt

LATER WORKS:

Around 1911, Klimt stopped decorating his canvases with gold leaf. Instead, he began incorporating intricate planes of kaleidoscopic color into his compositions, culminating in designs reminiscent of woven tapestries or inlay decoration. He deliberately painted allegories of life and death. While these works remain a celebrated part of his portfolio (Death and Life received first prize in the 1911 International Exhibition of Art in Rome), it is the glittering pieces from his Golden Period that seem to stand out from the rest.

LEGACY AND DEATH:

It is believed that he fathered somewhat around fourteen children with various mistresses, many of whom were the subjects of his sketches. Klimt never married but he did find a long-term partnership with Emilie Louise Flöge, whose sister was briefly married to Klimt’s brother Ernst before his untimely death. Flöge subsequently became his muse and lifelong companion. They would often spend their summers together at the Attersee Lake in the Austrian countryside where Klimt painted many of his landscapes.

Source: WikiCommons

After he was hospitalized for a stroke, Klimt died of pneumonia in 1918 at the age of 55. His vision of a progressive, freely expressive form of figurative painting perturbed the so-called lords of Viennese art and his work left an everlasting influence on the next generation of artists, especially during the Austrian Expressionist movement. The largest collections of Klimt paintings can be found in Vienna at the Belvedere Museum which has The Kiss. While the Vienna museum boasts the largest collection of Klimt drawings, in New York City, his work can be found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, and Neue Galerie, which houses his most famous portrait of Adele.

“Whoever wants to know something about me – as an artist which alone is significant – they should look attentively at my pictures and there seek to recognise what I am and what I want.”

―Gustav Klimt