Currently Empty: ৳ 0.00

Impressions of Monet

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Claude Monet became quite the prominent figure in the Impressionist movement, which revolutionized French art. Throughout this period Monet often painted picturesque landscapes and depicted the day-to-day activities of Paris and its neighboring areas, as well as the Normandy coast. He spearheaded the concept of modernism through the 20th-century with his unique art style that aimed to capture on canvas the very act of perceiving nature as is.

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

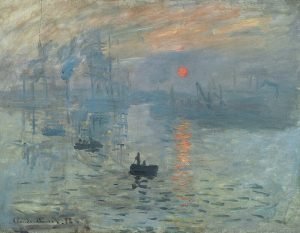

Monet was born in Normandy and was first exposed to the Plein-Air painting by Eugène Boudin, who was well-known for his works of the resorts that dotted the region’s coastline. He later trained informally under the Dutch landscapist Johan Jongkind from 1819 to 1891. Monet joined the Paris studio of academic history painter Charles Gleyre at the age of twenty-two, along with Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and others who would later become prominent Impressionists of their era. However, Monet enjoyed very limited success with only a handful of his landscapes, seascapes, and portraits that were approved for the show in the annual Salons of the 1860s. However, the rejection of several of his most ambitious pieces, such as the “Women in the Garden” (1866), spurred Monet to assemble his own exhibition in 1874, collaborating with Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Renoir, and others. One of Monet’s works to the show; Impression, Sunrise (1873), received particular criticism for the unfinished appearance of its loose handling and imprecise outlines. The painters, however, took the criticism as a badge of pride, and dubbed themselves “Impressionists” after the painting’s title, despite the fact that the term was initially used sarcastically.

“Impression — I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

– Claude Monet

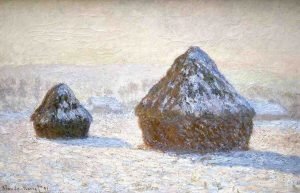

Part of the Heystack series by Claude Monet

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

Monet often drew inspiration for his work from his surroundings. Camille, his first wife, along Alice, his second wife, both acted as models for his work. His landscape paintings depict voyages across northern France and to London, where he fled the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. Upon returning to France, Monet settled in Argenteuil, barely fifteen minutes by rail from Paris, and later moved west to Vétheuil, Poissy, ultimately settling in Giverny in 1883. Manet and Renoir, his former associates visited his residences and gardens, painting alongside their host. Despite this, Monet’s paintings portray these settings with a refreshingly objective eye, with little evidence of domestic intimacy.

“For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life – the light and the air which vary continually. For me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere which gives subjects their true value.”

Following in the path of the Barbizon painters, who had set up their easels in the Fontainebleau Forest earlier in the century, Monet adopted and extended their commitment to close observation and naturalistic representation. Unlike the Barbizon painters, who only painted preparatory drawings en Plein air, Monet often worked straight on large-scale paintings outside, then returned to his studio to revise and finish them. His desire to represent nature more realistically led him to abandon European composition, color, and perspective standards.

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

Monet’s asymmetrical compositions of patterns, influenced by Japanese woodblock prints, highlighted their two-dimensional surfaces by removing linear perspective and forsaking three-dimensional modeling. By employing unmediated colors, adding a range of tones to his shadows, and prepping canvases with light-colored primers instead of the black grounds employed in conventional landscape paintings, he gave his works a dynamic brightness.

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

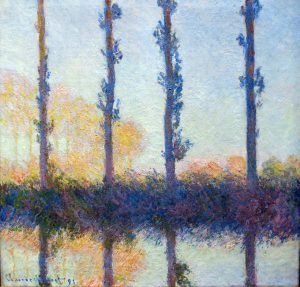

Monet’s fascination in capturing perceptual processes hit its peak in the 1890s with his series paintings (e.g., Haystacks [1891], Poplars [1892], Rouen Cathedral [1894]). Monet painted the same place over and over in each series, capturing how its look altered with the passing of time. In his Rouen Cathedral series, light and shadow appear to be as real as stone. In 1892 and 1893, Monet rented a chamber across from the cathedral’s western face, where he worked on many paintings and switched from one to the other as the light changed. In 1894, he completed the works by reworking them.

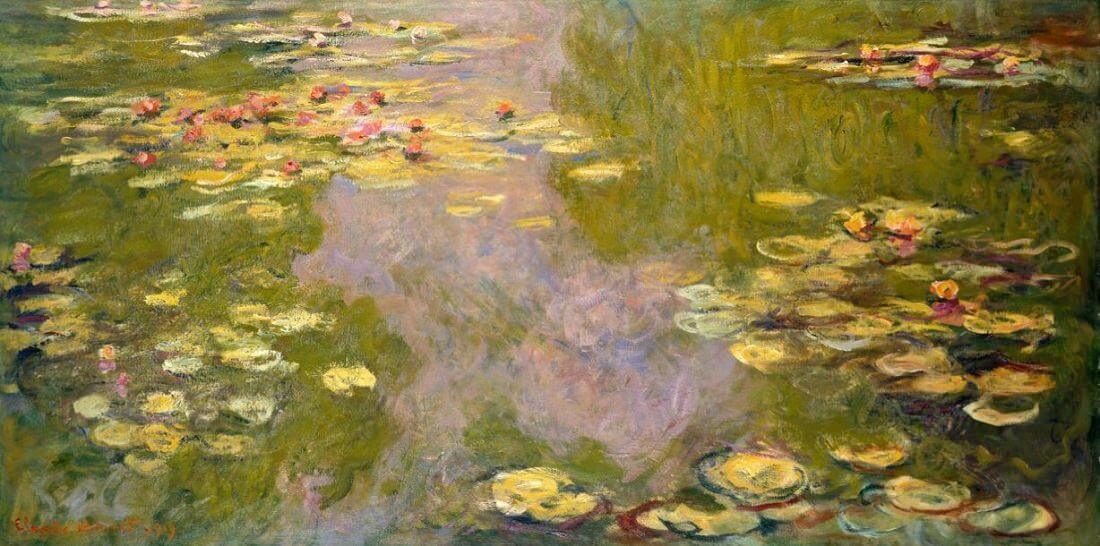

During the 1910s and 1920s, Monet concentrated almost entirely on the lovely water-lily pond he built on his Giverny estate. In his last series, he represents the pond in a series of mural-sized paintings, where wide strokes of color and delicately built-up textures reveal abstract depictions of plants and water. Monet died at the age of eighty-six in the year 1926. Upon his death, the French government installed Monet’s final water-lily series in specially constructed galleries at the Orangerie in Paris as a tribute to this French Maestro.

Courtesy of www.Claude-Monet.com

“Everyone discusses my art and pretends to understand, as if it were necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love”

– Claude Monet